RouteFinder

Choosing the Right Sport Climbing Route for You

by Jake Present, Kiera Berger, and Casey Boland

What does it take to become a better sport climber? If you could teleport to any climbing area in the United States, where should you go?

What differentiates a route with a beginner level YDS (Yosemite Decimal System) rating from one an advanced climber can send? Is it technical skills? Raw strength? Endurance? Grip strength and form?

Using data scraped from the MountainProject database in August 2020 and hosted by openbeta.io, we’ve analyzed the climber-entered descriptions for each route to determine what skills a climber needs to possess to successfully climb at a higher level.

Take a look at this map of the more than 54,000 sport climbing routes entered in MountainProject, with the color of each point corresponding to the difficulty rating assigned to it. In the rock climbing world, a low YDS rank corresponds to an easier route, while the routes with higher YDS ranks are more challenging. The distribution of the route locations is not exactly surprising, with the vast majority of them seeming to be located around the Appalachians and the Rockies, depending on which coast you happen to live on.

Unfortunately, while this view of the data is interesting, it doesn’t give our hypothetical climber much of an idea of which route to pick. With this many routes, there are likely infinite combinations of hold type, rock shape, and climbing style.

The Data

In the rock climbing community, difficulty ratings for climbing routes range from 5.0 to 5.15, with +/- or a/b/c/d modifiers to further expand the scale. For simplicity, we’ve divided these into the following four groups:

5.10a and below: Beginner

5.10a/b through 5.10d: Intermediate

5.11a-d: Advanced

5.12a and above: Elite

To learn more about what the original ratings mean, you can visit this page.

As you can see in the pie chart above, each category contains a roughly equal number of routes.

Keywords of Potential Interest

Route descriptions entered into MountainProject are packed with rock climbing slang that, while providing great opportunities for analysis, can be difficult for a newcomer to understand. Some words will be explained along the way, and we’ve included a brief glossary at the end for the rest.

After filtering out filler words, such as prepositions, articles, etc. from the route descriptions, we identified 88 words as potentially interesting and useful for our analysis. Some common words, like “angle,” were excluded because they could have a wide range of meanings depending on context.

The word cloud above shows how many times each word appears in the dataset. The size of each word represents how common a given word is the overall dataset, while the color of the word represents how common it is in the selected category.

Keywords Common Between Categories

In the above view, if you sort the words by the “Beginner” difficulty category, you will see the words sorted by their frequency in easier routes. You can see how certain keywords pertain to different difficulties. For example, the word “slab” is more common with beginner routes, and becomes less common as the difficulty increases. This is due to the fact that “slab” references a route that is fairly straightforward and vertical, which helps to make a route easier.

On the other hand, a route with more “roof” elements is increasingly more common in harder routes, because a roof is more horizontal, which requires a climber to be more parallel to the ground when they climb this section. Climbing a roof requires a great deal of effort, which is why it seems to be associated with more challenging routes.

Climbing Skills Required

There are 3 main skill types involved in climbing a route. Endurance is necessary to sustain long periods of effort along a route, especially routes that are longer from start to finish. Technical ability refers to a climber’s knowledge and practice of moving their body in the ideal way for the specific rock formation surrounding them. Power is generally associated with the climber’s maximum strength, which becomes important in performing dynamic, fast changes in body position on a rock face.

Twenty-four of our selected keywords have a clear association to one or more climbing styles. We used these words to calculate a Technical Score, Power Score, and Endurance score for each route. Representing these scores as a percent of the total score for a route, we can visualize the style trends in the ternary plots below. The score quality represents the total score for a route (range 2.1 - 103.4), with higher scores indicating that a route description includes words with stronger association to style such as the literal style word.

Click the buttons along the bottom to view how the climbing requirements change as the difficulty increases. In the beginner routes, a climber must have a basic level of endurance, technical ability, and power. The plot is relatively sparse, meaning that many of the beginner routes do not utilize these skills enough to warrant inclusion in the description.

As the difficulty increases, so do the number of routes that use description words associated with one or more of these styles. Challenging routes require dedication to hone these skills, and as you can see in the Elite category, all three skills are heavily represented throughout the plot. Perhaps more notable, however, is the concentration of routes in the center. While there are very few balanced routes at the beginner level, more difficult routes are most likely to require a combinationn of two or even all three skills.

Physical Features of Routes

Types of Hold

A hold is a rock climbing term for the places on the rock surface that are shaped in a way for a climber to attach themselves to the route and propel themselves higher.

A crimp is a type of hold that consists of a small edge that can support the tips of a climber’s fingers. Jugs are large, deep, concave holds that are relatively easy to grab with one or both hands. A knob or pinch hold can be “pinched” between a climber’s fingers and thumb, and requires intense strength to grasp. Pockets are holes within a wall that a climber can use to insert their hand or fingers. Slopers are large, round holds that can be difficult to grip and do not have sharply defined edges.

In the above view, you can see how the hold types vary by difficulty level. Click on the buttons to the right to change which hold type is lined up along the x axis.

Crimps are a type of hold that is rather difficult to grasp, so crimps become more common as the difficulty increases.

Jugs are the opposite: since they are easy to grab, jugs are common among easier routes and are less present in challenging routes. Easy routes are correlated with the presence of jugs.

Interestingly, knob and pinch holds make up a greater proportion in the beginner routes than the intermediate and advanced routes. As visible in the “Keywords Separated By Category” bar graph shown earlier in this page, knob holds specifically are more common with easier routes, while pinch holds are more common with harder routes. Though they are a very similar type of hold which is why we grouped them together, the relative roundness of knob holds compared to pinch holds potentially makes them easier to grasp and therefore more likely to make a route easier.

The elite routes predictably have the highest percentage of slopers, which makes sense due to slopers’ tendency to be incredibly difficult to grasp. Based on this data, slopers seem to make routes harder.

Types of rock shape

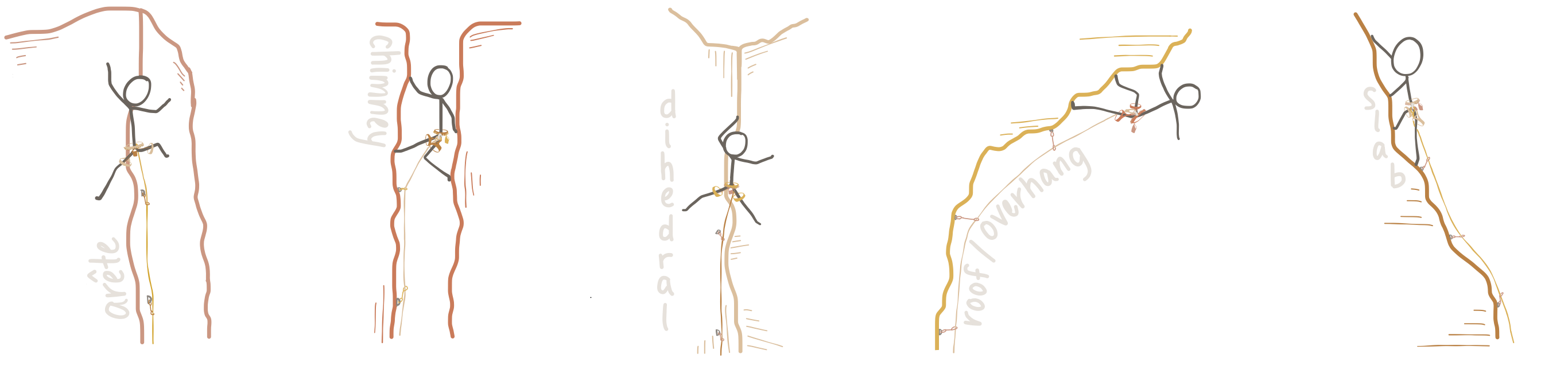

We have identified 5 different route shapes common among the routes in our dataset. In addition to slab and roof elements, common route shapes include arete, chimney, and dihedral features.

Overhang can be considered a less extreme version of a roof, where it is a rock face angled towards the ground, but not as parallel to the ground as a roof would be. Arete routes contain an edge or outer corner along its side, while a chimney refers to a section of rock with at least 2 parallel faces on which a climber can place their hands and feet to leverage the opposing forces. Dihedral routes involve two intersecting faces of rock that form an angle. It can be thought of as an inside corner.

This view highlights the different rock features that are present in the difficulty categories. We knew from the keywords visualization that the slab shape of a route is more common with easier routes and that roof elements are more common with difficult routes, but here we can see the overall proportions of routes in each category that contain such features.

A whopping 53.3% of elite routes contain roof or overhang elements, compared to only 27.35% of beginner routes. On the flipside, only 19.65% of elite routes are slab-shaped, compared to beginner routes’ 41.68%.

From this view, we can determine that it is likely that slab and chimney elements of a route help to make it easier to climb, while roof & overhang make it more difficult.

As for dihedral and arete features, their presence seems to be evenly distributed among the difficulty categories. Based on that observation, it is likely that these features vary in difficulty and do not necessarily contribute to causing a route to be easier or harder.

RouteFinder: An Interactive Map

Revisiting the initial map of all routes, it is now much more interactive. Using what we have learned so far about what makes a route easier or harder, you can filter the map based on hold types and rock shape, as well as by pure difficulty ratings of course. Also, you’ll notice that a small jitter has been applied for routes in the same location, so all should be visible if you zoom in.

Ultimately, each climber is unique and likely has or will develop their own personal preferences regarding what they’d like to climb. We hope that this final map view will enable prospective outdoor climbers to review potential spots with more information than just the difficulty level and choose the right sport climbing route for themselves.